ECOLOGICAL HISTORY

Many of the trees now present on the Tionesta Areas are

several hundred years old, and we have no information about the early ecological

history of the area. Forests of essentially the same type may have existed

on this tract for a very long time.

However, studies of ecological succession show that the

forest now present is a climax community. It consists primarily of species

that are tolerant of shade, such as hemlock, beech, and sugar maple.

Seedlings of these species are capable of surviving for years beneath the canopy

of larger trees. Then, when an overstory tree matures, dies, and falls to

the ground, it releases enough growing space for some of the tolerant seedlings

present in the understory to grow and eventually reach up into the main crown

canopy. In this way, a stand of shade-tolerant tree species is

perpetuated.

But fire, windthrow, and other disturbances occasionally kill

many trees in small areas, creating larger openings in the forest canopy than

result from the natural death of scattered individual trees. When this

happens, tree species that are light-demanding (shade-intolerant) are also able

to get started. Since these species usually grow faster than the

shade-tolerant species, they overtop the tolerants and may dominate the site for

50 to 100 or more years. Black cherry, red maple, yellow birch, black

birch, white ash, cucumber-tree, yellow-poplar, and pin cherry are examples of

shade-intolerant trees that originate after forest disturbances.

If left undisturbed long enough, the intolerant species will

gradually be replaced by shade- tolerant species, because the intolerants cannot

survive for long under their own shade. Hence large seedlings of

these species are not usually present to make use of the small openings that

occur from the death of scattered individual trees. Most of the Allegheny

Plateau outside the Tionesta Scenic and Natural Areas is now dominated by

second-growth stands of intolerant species resulting from the commercial logging

operations of the 1890-1930 era. These second-growth stands will

eventually revert to hemlock/beech/sugar maple types like those in the Tionesta

tract if left undisturbed long enough.

Because climax forests generally contain a number of

overmature low-vigor trees, natural disturbances of one kind or another can be

expected occasionally. Documentation of such disturbances in the Tionesta

tract is limited, but there is some information available about this and nearby

areas.

Climatic effects

Strong winds occur periodically in this area, but the

damage they do is usually limited to small groups of trees. Occasionally,

however, wind storms damage extensive areas. About 1808, timber was blown

down on the southern edge of the Research Natural Area. In 1870, many

trees were uprooted on about 375 acres by a wind storm that struck the southern

edge of the Scenic Area. The affected areas reverted to a secondary

successional stage in which shade-intolerant second-growth species flourished

along with the shade-tolerant hemlock and beech that survived.

In areas close to the Tionesta tract, many mature hemlocks,

beech, and trees of other species died after the serious and widespread drought

of 1930. Many other hemlocks, weakened by drought, were attacked by the

hemlock borer (Melanophila fulvoguttata Harr.). A local but severe

early summer drought occurred in 1934, and hemlock mortality was observed a year

later. Important but hidden effects of these droughts are a slowdown of

Page 5

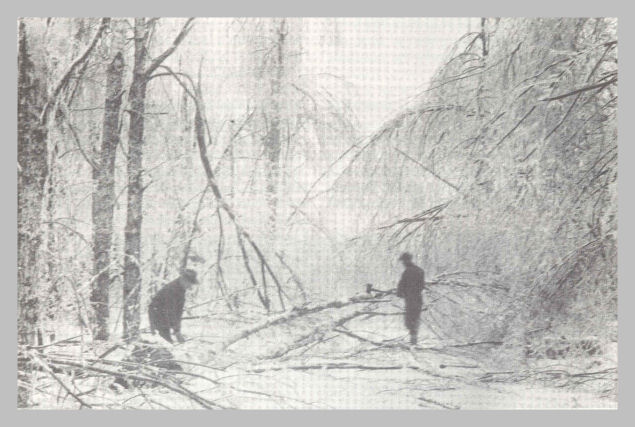

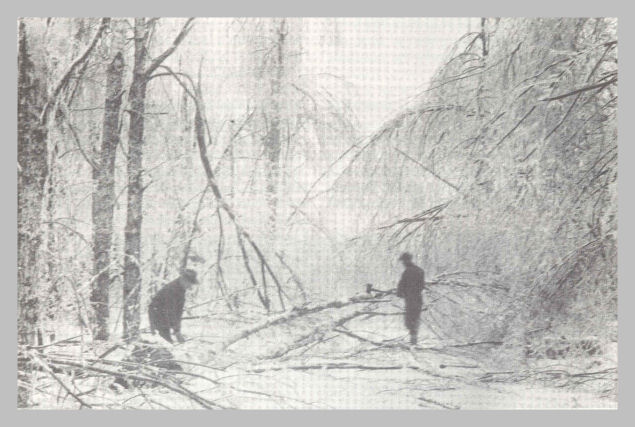

Figure 6.-ln the glaze storm of March 1936, trees and branches broke under the weight of the ice. Evidence of this glaze damage can still be seen in the broken tops of many trees.

growth and a slowdown of regeneration through seedling mortality or the

failure of seed crops.

Ice storms are fairly common on the Allegheny Plateau.

Normally they cause little damage; yet heavy and extensive damage has occurred.

In the severe ice storm of March 1936, which covered most of the Allegheny

Plateau, trees and branches came crashing to the ground (fig. 6). Twigs

the diameter of a pencil were ringed with coats of ice 2 to 3 inches in

diameter.

Black cherry was severely damaged by the ice in that storm,

Red maple, beech, and the birches suffered some damage; sugar maple was damaged

less. Hemlock suffered little damage, presumably because of its resilient

branches and smaller upper crown.

Some small changes in species composition may have occurred

because of these differences in species susceptibility. Black cherry

probably represented a relatively smaller proportion of the stand after the

storm, while the other species benefited at the expense of the cherry. The

relative amount of hemlock increased, but the maples and birches were affected

less. Individual trees of all species were deformed. Broken tops and

branches left open wounds that were susceptible to insect and disease attack.

These are long-term effects. Evidence of the 1936 storm is still visible

after 40 years, and it will not be gone until the affected trees have died.

Fire

Although the 1870 blowdown was later swept by fire, fires have rarely occurred in the Tionesta tract-probably because of the moist nature of the forest floor, lack of inflammable undergrowth, and isolation of the area. In 1930, an examination of the area lying north of Cherry Run showed no evidence of past fires. And it appears unlikely that any part of the Fork Run drainage had ever burned.

Biological effects

Harmful insects and diseases commonly found in forest

stands have always been present on the Tionesta tract. Each can damage and

destroy roots, flowers, and seeds; each can injure or kill young seedlings and

mature trees; and each can cause a loss of vitality and reduction of growth.

But there is no evidence that either insect or disease attack has been severe

enough to affect the composition of the hemlock-beech forest on this tract.

Most of the animal damage has come from two creatures-the

porcupine and the white-tailed deer.

Porcupines-feeding on the bark, cambium, twigs, and

leaves-kill or damage trees by girdling the stems and cutting off branches.

Record from the 1930 survey showed some incidence of porcupine damage on 40

percent of the plots measured. The greatest damage was done to beech,

hemlock, black cherry, sugar maple, and yellow birch, in that order.

Porcupine damage, usually scattered throughout a forest stand, often occurs at

hard-to-see locations such as tree tops. For this reason, the damage may

not be very noticeable unless several porcupines are feeding in the same area.

Deer pose a special problem. Pennsylvania's deer herd

was nearly eliminated about 1890 because of unlimited hunting. But public

interest stimulated a number of positive actions in the early 1900s that favored

the deer herd-notably the formation of a game commission, the restocking of the

herd with out-of-state deer, and the passage of a "bucks-only" hunting law.

These measures coincided with extensive, timber-harvesting throughout

northwestern Pennsylvania, which increased production of browse. Thus,

protected and well-fed, the deer population increased rapidly.

About 1930, the young second-growth stands, that developed

after this timber harvesting grew up out of the reach of the deer.

Available browse was very limited. Despite the limited amount of browse,

the deer herd continued to increase, reaching a peak several years later.

In this period, vegetation within reach of the deer was continuously

overbrowsed.

Between 1932 and 1942, the understory of hemlock and hobble

bush declined on all portions of the Tionesta tract because of repeated heavy

browsing. Other tree species, shrubs, and herbs were also browsed.

Tree species palatable to deer include hemlock, black and pin cherry, and red

and sugar maple. Favored shrubs include hobble bush, the elders,

wild-currant, blackberry, and raspberry. Herbs used as forage are many and

varied.

Because of this intensive and selective browsing, the

relative number of unpalatable beech seedlings and root suckers increased on the

Tionesta tract. If such browsing is continued over a long enough period of

time, the regeneration of hemlock, the maples, and black cherry may be

prevented; and the species composition may be modified toward a nearly pure

beech stand.

The effect of inadequate browse is noticeable on the deer

too. Deer are smaller than normal; antlers are poorly developed.

Weakened deer starve, and mortality is high, especially in severe winters.

These conditions, along with frequent doe seasons and more hunters, reduced the

deer herd to a relatively low level about 1950. But since that time, the

number of deer has been increasing, and the browsing conditions of the past may

be repeated. Clearly there is a need to manage the deer herd to maintain

its size and well-being commensurate with the available supply of nutritious

browse.

Influence of man

Although the Tionesta Scenic and Research Natural

Areas have never been logged, man has had an impact on the forest. The

discovery of oil near Titusville in 1859 and the opening of the Tidioute oil

field in 1860 was followed a short time later by the drilling of oil and gas

wells within the present boundaries of the Tionesta tract. The wells-along

with the necessary pump houses, storage facilities, service roads, and pipe

lines (the first one installed about 1904)-have left their mark (fig. 7).

Today, some wells are still producing while others are used for gas storage.

Most of these wells are on the height of land between the Cherry Run and Fork

Run drainages, but some are within the drainages themselves.

Drilling and attendant activities can continue indefinitely

because the oil, gas, and mineral rights are in private ownership-only the

surface rights are owned by the Federal Government. However, the private

owners have cooperated with the Government to reduce the effect of these

activities on the Tionesta forest.

Page 7

The imprint of man on this virgin forest will remain for a long, long time, because the openings created by the oil and gas operations are actively maintained and so will not revert to forest. Some of these openings have revegetated with ferns, grasses, and herbs. Although they are unnatural openings in a virgin forest, they add diversity to the plant life and are attractive to wildlife.

Figure 7.-Although pipe lines are artificial openings in a natural setting, they open the area to hikers and gradually take on the appearance of a forest trail.

Page 8