Page 26-50

[Note from the web master. The word heal may be used

here to describe the closure of a wound. Dr. Shigo now calls it closure and not

healing. That and other terms can be found at

www.treedictionary.com for your use.

John A. Keslick , Jr.]

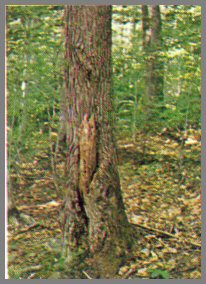

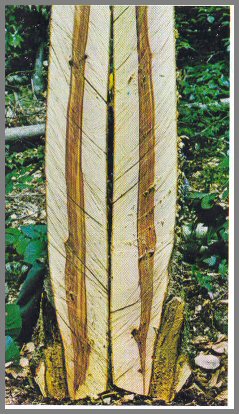

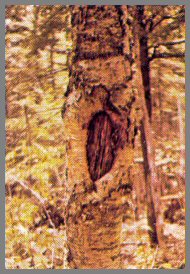

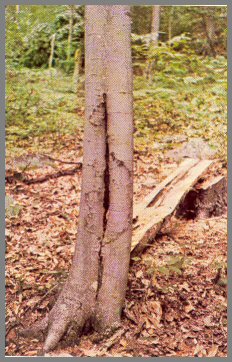

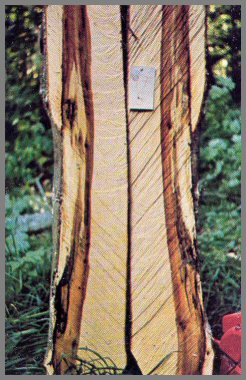

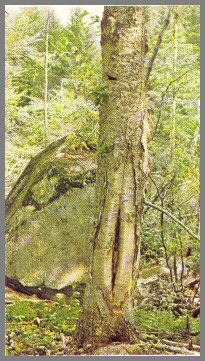

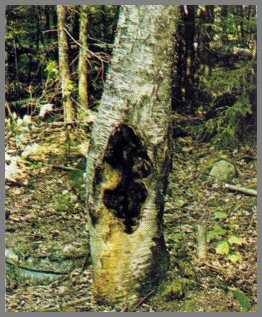

FIGURE 8. - BASAL STUB ABOVE ROOT COLLAR

On this red maple tree a low basal stub joins the stem above the root collar. The color and feel of the stub indicate that discoloration and decay are associated with it. The diameter of the stub indicates the diameter of the defect column. Note also a small healed wound above the stub.

Dissection reveals the decay and discoloration in the base. The pattern illustrates the sequence of events in the discoloration and decay processes. The column of discoloration at the top is sound and dry, and no organisms are present. Below, the discoloration is darker and moist (blackheart), and contains organisms that do not cause decay. At the bottom is the dark moist core of decay, which contains decay fungi. The small island of discoloration above is due to the small wound.

Page 26

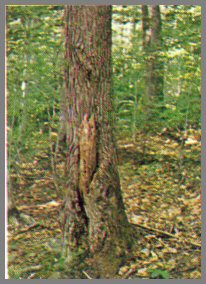

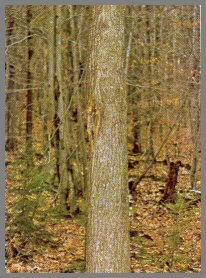

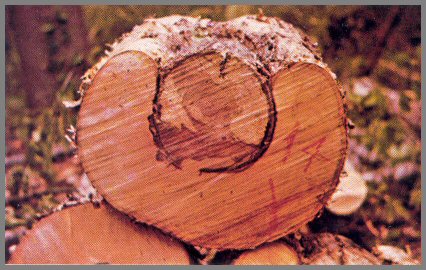

FIGURE 9 - BASAL STUB ROOT COLLAR

The large decayed stub on this yellow birch is joined to the stem below the root collar. This position, plus the angle of the stub, indicates that the decay does not go into the main stem.

Dissection shows that the decayed stub is separate from the main stem and does not affect it. The central column of discoloration marks the diameter of the tree when most of the branch stubs above died.

Page 27

FIGURE 10. - SPINDLE-SHAPED CANKER ON STUB

The spindle-shaped canker, on this red maple formed after the branch stub was infected with Polyporus glomeratus, one of the principal fungi that infect red maple and sugar maple and cause cankers and decay. Sometimes a swollen area forms about the stub. The decay column usually becomes more extensive as it moves up the stem and meets other columns from higher branch stubs, then dwindles in size as it reaches the crown. The fertile stage of this fungus forms on dead and down trees, and the entire stem of a dead tree may be covered with fruit bodies in the fall.

Dissection reveals advanced discoloration and decay. Discoloration occurs first; then P. glomeratus infects the discolored wood. After the fungus becomes established, it kills the bark about the stub, thus forming a canker.

Page 28

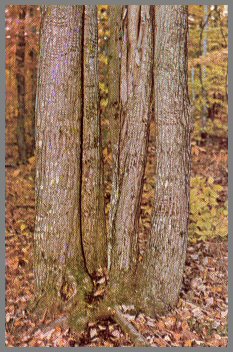

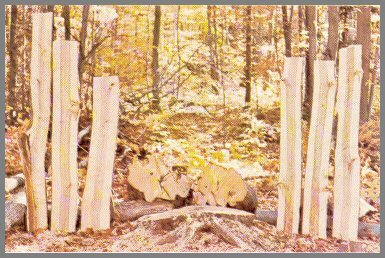

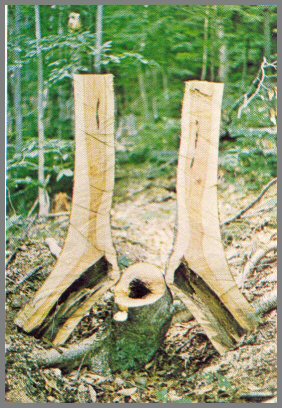

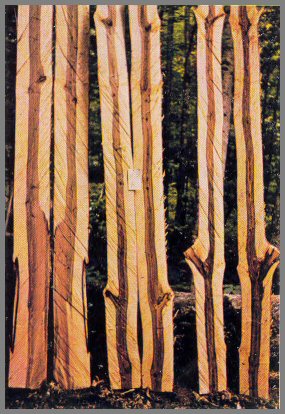

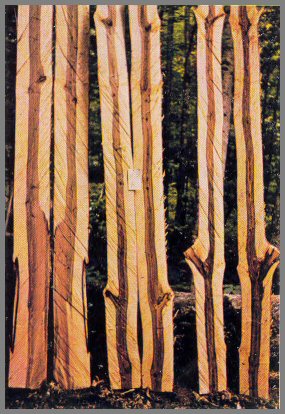

FIGURE 11. - SPROUT CLUMP

A typical red maple: sprout clump, formed low on the old parent stump. The parent stump decayed rapidly, so there is little connection between the old stump and the sprouts. If a sprout stem has many poorly healed branch stubs, it has little future value. But if the stubs are small, few, and well- healed, the sprouts can have good future value even if the base looks poor. The poorer sprouts can be cut without causing damage to the remaining sprouts.

Dissection shows that the base is sound, but all the stems have discoloration and decay due to branch stubs. The section at extreme left has a decayed stem stub. The next has a Poly porous glomeratus canker; the decay is light- colored, and the rim of the column is dark. All three sections on the right are infected with P. glomeratus.

Page 29

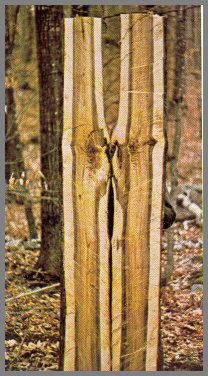

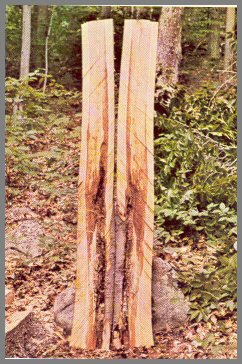

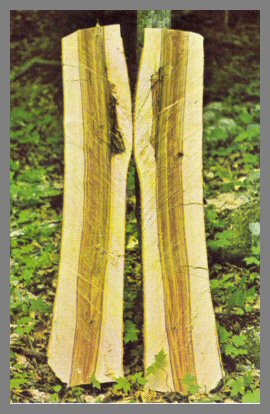

FIGURE 12. - STEM STUB

This sugar maple has a stem stub, where once the main stem broke and a branch became the new leader. Such stubs catch and hold water, and this is why they result in more damage than branch stubs of the same size and age. Sound stem stubs indicate discoloration; decayed stem stubs indicate advanced discoloration and decay. Stem stubs are usually found between 4 and 16 feet up the stem.

Dissection shows the pattern of defect from this stem stub. The wood is damaged more near the stub because this area has been affected longer. The discoloration is the diameter of the stub, and it spreads downward. The upper part of the discoloration is blackheart; the tissues are moist and infected with organisms. The lower part of the column is lighter in color, drier, and contains no organisms. The small core of defect in the new leader is due to branch stubs in the new leader.

Page 30

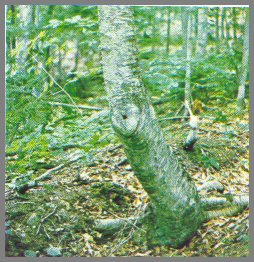

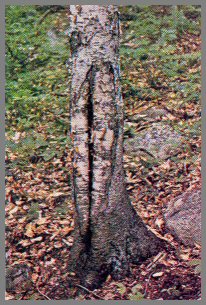

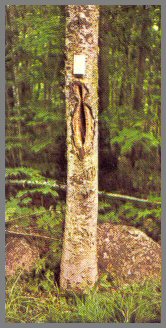

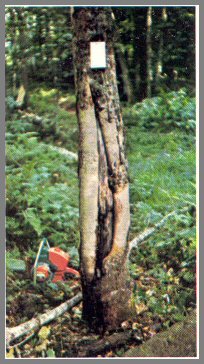

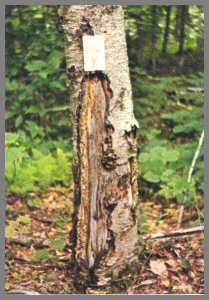

FIGURE 13. - DECAYED STEM STUB.

The stem stub on this yellow birch decayed; and all that remains is an unhealed stub hole, indicating that the stub has been present a long time. Stem stubs like this are common on birches that have been broken by heavy loads of ice or snow. The discoloration and decay processes have had a long time to work on this tree.

Dissection shows that the older leader has completely decayed. Yet the decay fungi did not advance out into the new tissues. The columns of discoloration that formed later enveloped the old defect column.

Page 31

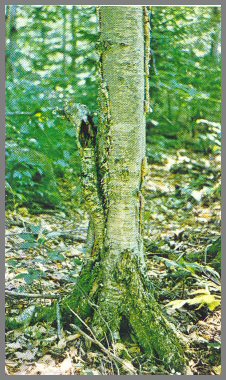

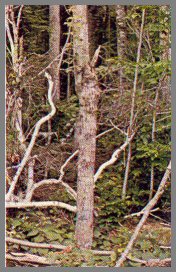

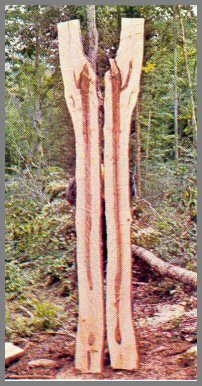

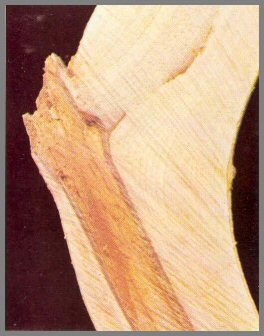

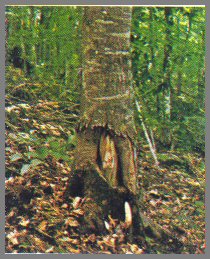

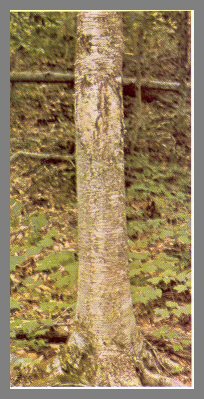

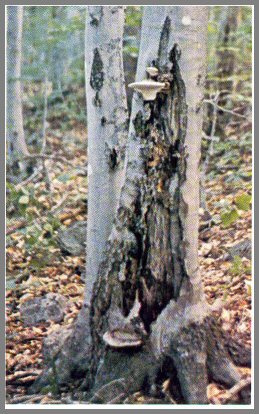

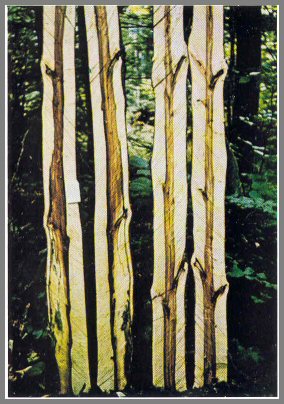

FIGURE 14. - STEM STUB IN BEECH

In this beech tree the original leader died at the 5- foot level.

Even though the stem stub completely decayed and the tissues below were

decomposed, the base of the tree contains very little defect. In

beech, columns of defect narrow abruptly as they approach the base.

The boundary of the discoloration column is white in beech.

Close-up of a dissected stem stub in beech. Even though the stem stub is decayed, the boundary of the decay is a hard rim, a barrier zone between the defect and the white wood.

Page 32

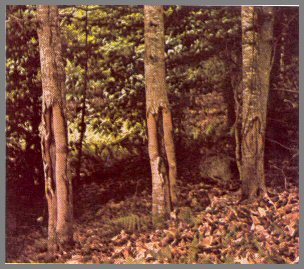

FIGURE 15. - LOGGING WOUNDS ON SUGAR MAPLE

These three sugar maples were wounded by logging equipment, 8 years earlier. The tree on the right is dead; it had severe root wounds. The other two have good callus growth, which indicates vigorous growth; and the well- healed stubs indicate that the wounds, though severe, did not produce extensive decay.

Dissection shows that the dead tree did not develop discoloration. In the other two trees, decay was present, but the defect ended abruptly above the wounds. The defect was wedge-shaped in cross-section. Because the trees had small, well-healed stubs, no central column of discoloration developed; and the wood was white from bark to pith.

Page 33

FIGURE 16. - LOGGING WOUND ON YELLOW BIRCH

A severe old logging wound on a yellow birch. The face of

the wound is decayed, indicating decay in the tree.

The cross-section shows the effect on growth of the tree. The 2-inch

central hard core of discoloration was already in the tree when it was wounded

at 6 inches. The discoloration and decay due to the logging wound did not

penetrate the smaller defect column. This is another example of multiple

columns of defect in living trees. Just as they do not advance out into

new tissues, the discoloration and decay also do not penetrate tissues affected

earlier.

Page 34

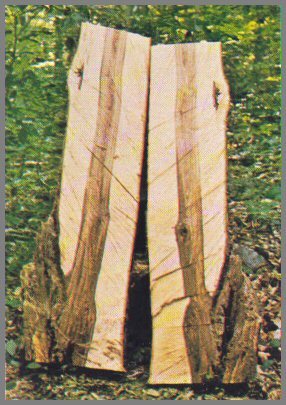

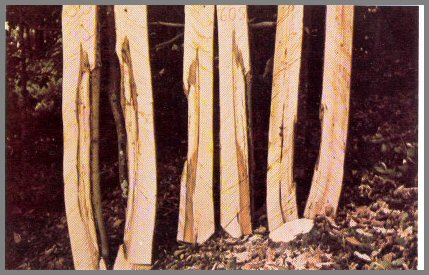

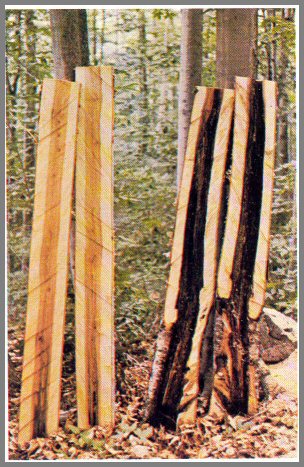

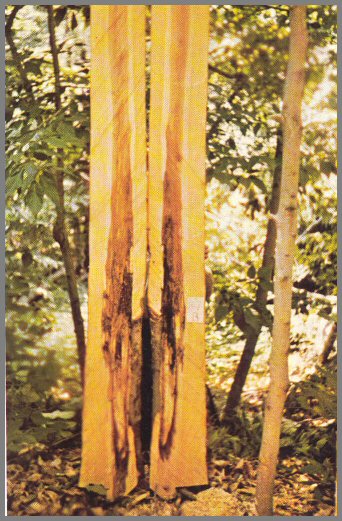

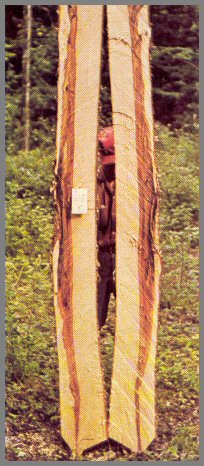

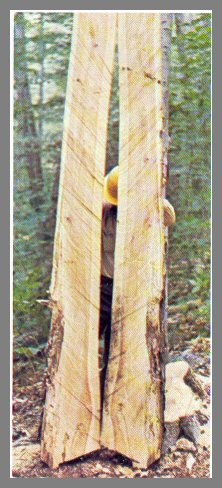

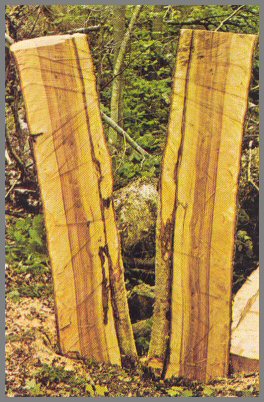

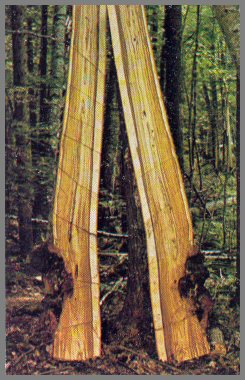

FIGURE 17. - LOGGING WOUND ON PAPER BIRCH

This 1OO-year old paper birch has a 50-year-old wound, which extends to the base of the tree. There is a wound of similar size and age on the opposite side of the tree.

Dissection of the tree to 16 feet. The lower 8-foot section ( right) has a 5-inch hollow center. Yet the decay did not go into the new wood formed after the tree was wounded. In the upper 8-foot section (left) the advance of the decay fungus can be seen as dark streaks in the wood.

Page 35

FIGURE 18. - LOGGING WOUNDS ON BEECH.

A 1OO-year-old beech tree with a 50-year-old wound, which does not extend to the base of the tree. The hollow behind the wound indicates advanced decay.

Dissection shows that, although the decay is advanced, the base is free of decay. The decay column narrows abruptly above the wound. The boundary of the column is white. The decay advances farthest as a streak above the wound site.

Page 36

FIGURE 19. - LOGGING WOUND ON BEECH.

This beech tree had a single wound above the base. Dissection shows that the base is clear, but discoloration and decay spread upwards. The decay fungi advanced through tissues first infected by other organisms; and decay was limited to these tissues. A white band surrounds the column of discoloration but not the decay column near the wound. The tissues in the white band contain plugged vessels.

Page 37

FIGURE 20. - LOGGING WOUNDS ON RED MAPLE.

This red maple has two 8-year-old wounds, the smaller on the left facing the sun, the larger on the right mostly in the shade. The face of the small wound is white; the face of the larger wound is dark. Dark wound faces indicate more defect than light wound faces.

Dissection shows the difference on the lower 8- foot section at left. Very little defect is associated with the small white wound. But the defect caused by the larger dark wound meets the central column of discoloration from the branch stubs. In the upper sections of the tree, the larger branch stubs give rise to dark, moist discoloration and decay. Many stages of discoloration and decay processes can be present in the same stem.

Page 38

FIGURE 21. - WHITE-FACED WOUND

This white-faced wound, on a sugar maple with well-healed branch stubs, indicates very limited defect. The face of such a wound is hard, and often has tan streaks.

Cross-sections through the wound and directly above it show that the defect was limited to the wound area and did not advance above it. The discoloration did not go into the tree center. The small central defect column indicates that the tree lost most of its branches when it was about 3 inches in diameter. The white zone around the central dark columns contains wood with plugged vessels. These tissues are drier than the other tissues.

Page 39

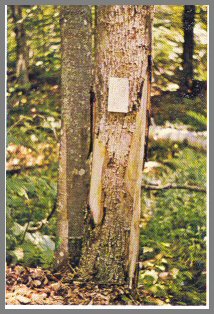

FIGURE 22. - WELL-HEALED SMALL WOUND

This yellow birch has a well-healed wound at 5 feet. On vigorous trees

shallow narrow wounds like this heal fast. Areas of smooth bark should be

checked to determine whether a wound is present.

Dissection shows that hard dark tissue and wavy grain are associated with the

wound. The large central defect column indicates that many branch stubs

did not heal till late in the life of the tree.

Page 40

FIGURE 23. - OPEN WOUND.

An open 9-year-old wound on a yellow birch with well-healed

stubs. The callus and healed stubs indicate a vigorous tree.

Dissection reveals redheart associated with the wound. The "infected tissues are dark red, moist, and contain decay organ- isms. The defect column narrows abruptly as it approaches the base of the tree. A well-healed stub is present several feet above the wound.

Page 41

FIGURE 24. - ROUGH DARK WOUND.

This sugar maple has an 8-year-old wound. The callus tissue is healthy. But the face of the wound is rough, dark, and splintered; and this indicates that the defect may be serious.

Dissection shows decay typical of Hypoxylon rubiginosum. The dark,

moist column of discoloration is wetwood or blackheart; it extends up to a

branch stub at 8 feet. Note that the decay is advancing through the

discolored column. In cross-section the defect area is wedge- shaped.

Page 42

FIGURE 25. - FOMES APPLANATUS

This beech tree has a large basal wound on which can be seen fruit bodies of Fomes applanatus, which indicates advanced decay, extending to base and roots. In beech, this is the principal fungus that infects the base. The face of the wound is dark and rough.

Dissection shows that decay extends from the base to 4 feet above the wound, where it ends abruptly. The central column of defect is very wide; this is due to the large wound and the infection of the tree base by F. ap

planatus.Page 43

FIGURE 26. - FOMES IGNIARIUS ON WOUND.

This beech tree had a fruit body of Fomes igniarius at 4 feet. Dissection reveals that decay is extensive above, where it meets defect columns from branch stubs, and narrows toward the base. The decay column is surrounded by a dark band, which is moist and contains other organisms. In the lower section is a smaller defect column that formed when the tree was young. The later defect column enveloped this small column, but F. igniarius did not penetrate this small column.

Page 44

FIGURE 27. - FOMES IGNIARIUS VAR. LAEVIGATUS

A 160-year-old yellow birch with a 60-year-old logging wound. The wound surface bears flat brown fruiting bodies of Fomes igniarius var. laevigatus.

Dissection shows that the decay caused by F. igniarius var. laevigatus even after 60 years, has hardly penetrated the central column of discoloration that was formed before the wound occurred. Note that the discolored margin of the decay column is only on the wound side.

Page 45

FIGURE 28. - POLYPORUS VERSICOLOR ON WOUND

This yellow birch has a severe 8-year-old basal wound bearing fruit

bodies of Polyporus versicolor. This is one of the first decay

fungi to invade the dead wood on the face of a logging wound. The fruit

bodies, the dark wound surface, the splintered wound face, and the poorly healed

stubs indicate much defect.

Dissection to 16 feet shows the decay caused by P. versicolor on the lower margin of the wound, the decay caused by another fungus in the interior of the tree, and the central column of discoloration and decay associated with the branch stubs. The darker discolorations on the sections at left indicate wetwood or redheart.

Page 46

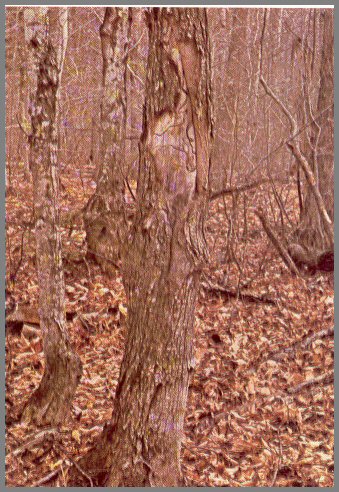

FIGURE 29. - PORIA OBLIQUA ON OLD WOUND.

This is a sterile conk of Poria obliqua on an old basal wound on a paper birch. The orange-tan ooze below the conk indicates moist decay. P. obliqua infection causes the tree stem to swell so it resembles a bowling pin. A tree! with this type of swelling can be identified at a glance as being infected with P. obliqua.

Dissection shows advanced decay caused by P. obliqua. The decay is darker and moister above the wound. This fungus can kill trees. It kills the bark slowly, and enlarges the wound. The fertile fruit body forms in the wood beneath the bark of dead standing trees. Trees infected with P. obliqua should be felled and left on the forest floor.

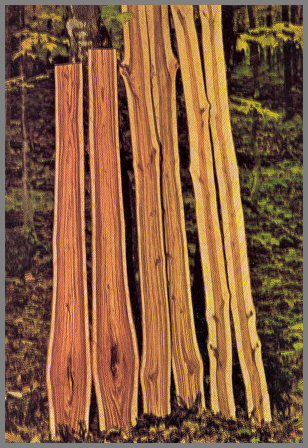

Page 47

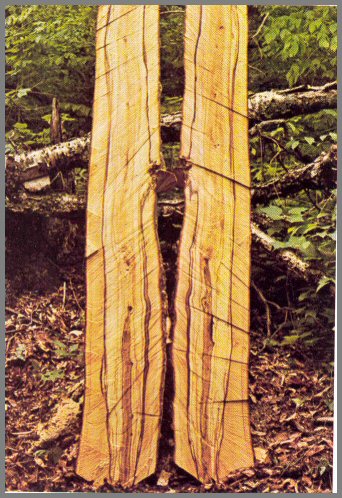

FIGURE 30. - BOWLING PIN EFFECT FROM PORIA OBLIQUA.

Dissection of this paper birch to 24 feet reveals the typical bowling pin swelling (butt sections, at left) caused by Poria obliqua. Note the range in color. The butt section at left is bright orange-tan, the middle section is tan, and the upper section (right) is light orange to pink. The discoloration and decay are most advanced at the base. The dark rims of earlier defect columns are obvious. As P. obliqua kills tissues about the wound,- enlarging it, and as new branch stubs form, new columns form and envelop those formed earlier.

Page 48

FIGURE 31. - OPEN WOUND BY SUGAR MAPLE BORER.

When injury by the sugar maple borer is severe, large open wounds result. Then the galleries made by the borers can be seen on the wound face. The sugar maple borer (Glycobius speciosus) has a 2- year life cycle; and in that time it normally bores in a spiral path to the center of the tree and then bores its way out again. A number of events can halt a borer; and the severity of the wound depends upon how much of its gallery the borer completes.

Page 49

FIGURE 32. - SELECTIVE ATTACK BY BORERS

The sugar maple on the right was injured by the sugar maple borer at many points on the bole, but the tree on the left was not touched by them. This is common, but we do not know why. The injury done by the borer may be minor, causing no more than a small bump on the bark; or it may be a major wound, exposing the wood and the borer galleries. In an area where borer injury is common, small bumps on the bark may be signs of small aborted borer galleries. Discoloration, decay, and twisted grain are associated with these wounds.

Page 50